George Washington was famously well-traveled. His careers as a surveyor and soldier of the King gave him a detailed familiarity the Appalachians and Alleghenies. Riding at the head of the Continental Army brought him to and through cities and communities all along the eastern seaboard, and once elected president he used travel as a way to see and be seen by the people of the new United States.

Walter Kerr Cooper’s imagining of GW in Barbados.

But for all of this travel, he only left the continental US once in his life. For four months at the end of 1751 he accompanied his sickly brother Lawrence to the British Colony of Barbados. The trip was meant to address his older brother Lawrence’s weak lungs by bringing them from Virginia to the softer, breezier, less humid, supposedly more healthful air of the Caribbean. Lawrence’s problems had actually begun years earlier in the Caribbean, but the view that changing one’s air could change one’s health was one was tenet of one of the competing regimes of medical logic confronting an ailing eighteenth-century Briton looking for relief. The Washington brothers had already traveled up to the Appalachian foothills to seek out the warm springs and cool dry air of what is now Jefferson County West Virginia. But that had limited effect at best. The Barbados trip was another attempt clean out, air out, and dry out Lawrence’s failing lungs.

And so it was that the two took bunks on a Barbados-bound vessel. There is some disagreement about just what ship this was. Some advocate a trip from a Potomac port aboard the Success, while others have argued that the sailed from Fredericksburg on the Rappahannock about the aptly named Fredericksburg. The George Washington Papers project at UVa and the Fred W. Smith Library at George Washington’s Mount Vernon are in the later stages of creating a new and probably authoritative edition of the small, damaged, and fragmentary journal Washington kept during his trip.

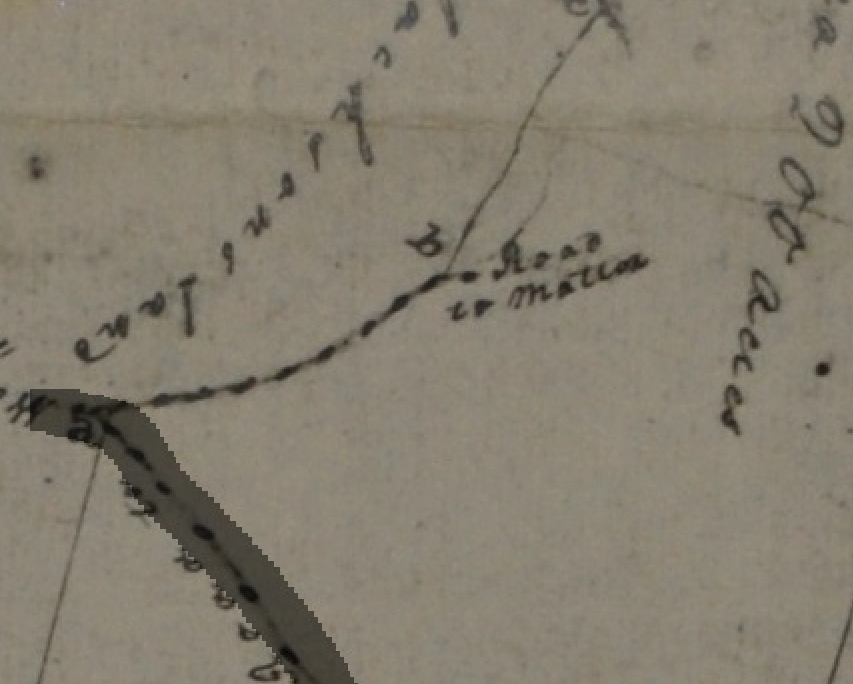

A little section of GW’s navigation note courtesy of The Washington Papers

Project Editor Alicia Anderson has made it her business to master enough trigonometry to be able to use Washington’s navigation notes to plot out the pace and path of the voyage. The chart she will create will go a long way towards settling the port of embarkation question. While we wait though, the most commonly read copy of the Barbados Journal is the one edited by J.M. Toner and published in 1892. It is full of oddities and errors, but it works. I have kept a copy of it on my phone so that I can refer to it on the fly while on the island. The George Washington Diaries also handled the Barbados Diary with a very good descriptive essay and a facsimile of the original which resides in the Library of Congress. The book I am now writing has a chapter on the Barbados trip and soon the new edition of the Diary will be out. Erin Holmes also will be pairing Washington’s homes and Barbadian homes in her University of South Carolina dissertation comparing plantation landscapes in Virginia, South Carolina, and Barbados, so GW’s time on the island is really happening!

The Brothers W arrived at Bridgetown in late October (or so it seems—the first actual entry on the island is dated November 4th, but pages before it are missing). They had a fairly calm crossing in which they enjoyed the swells of the sea and ate dolphin—a Caribbean favorite which smart marketers have renamed Mahi Mahi so that no one thinks they are eating a porpoise. In arriving at Bridgetown, Washington landed in the most cosmopolitan British city he had ever seen. The two colonies were roughly the same age, shared a somewhat similar history, had long-standing and extensive trade connections, and bore a superficial resemblance in government and society. Before sugar took over the island’s acres, planters had made a short- lived stab at tobacco planting hoping to recreate Virginians’ early seventeenth-century success. Like Virginians, Barbadian Britons could talk of an assembly, a governor and his council, they lived on plantations, and relied on enslaved African labor to keep themselves fed and have their fortunes made.

Henry Partleton’s 1880 photo of Bajan cane cutters. Partleton.co.uk.

On top of that, the mix of Britons and enslaved Africans was a bit like that found along Virginia’s rivers. But that was where the similarities ended. Bridgetown was nothing like any place in Virginia graced as it was with in-town homes of wealthy planters, an English-style church, well-built and fully manned military instillations, and large a Spanish and Portuguese descended Jewish community of merchants. An upcoming blog entry will deal a bit more with Washington and the Jews of Barbados. But even though Washington was something of a city kid by Virginia standards having lived most of his life at the doorstep of the small city of Fredericksburg, Bridgetown was something new.

The countryside was different as well. Sugar production led to a very different form of African enslavement and called into being very different cycles of labor. And Virginia was big: really quite big. That size—especially on its western edge—had already defined a significant part of the lives of the Brothers W and would soon offer even more. Even where Virginia settlement was dense it was never particularly crowded. By contrast, Barbados was a tiny island packed tight with actually fairly small sugar plantations and the distinctive stone windmills used to grind the valuable juice out of the cane. Washington noted that “scarcely any part” of the island “is deprived of a beautiful prospect both of sea & land.” (Toner, 58). He was correct, and his observation is of course still true today—but the many views only emphasize the tiny scale of the island.

But the young Washington was thrilled at what he saw on this grand adventure. On his trips into the countryside he was “perfectly enraptured with the beautiful prospects” which presented themselves to he and Lawrence and he marveled at the “fields of cane, corn, fruit-trees &c. in a delightful green”(Toner, 42). Washington took note of landscape and vegetation on these country forays. He commented on soil quality, the scale of sugar production, and agricultural practices. This was more than a mere curiosity. Sugar was a far more lucrative crop than was Virginia’s tobacco—partly accounting for why comparatively small island holdings could yield profits enough to even allow some planters to live well back in England. By way of context, a large Barbados plantation would be about 400 acres–that was the size that Washington said were the largest plantations. Henry Drax though owned 705 acres at the end of the seventeenth-century. His was one of the largest holdings on the island and one that allowed him to live back in England. On the other hand, John Dottin’s Mount Edge was 166 acres in 1759—a far more typical holding for a nice plantation. Plots of 10 acres though were not uncommon though. Compare that with the close to 1000 acres Washington inherited when his father died (himself owning l close to 10,000) of the 18,000 acres Washington took control of when he married Martha. Washington was just then making his first money though land surveying—an enterprise that rested on the availability of ever more new lands. To a Virginian, Barbados’s planters and their agricultural system working a tiny patch of land in the middle of nowhere seemed to hold the key to a sort of magical alchemy for making a fortune. At the same time though, Washington seemed astounded that so many planters were in debt or even lived poorly–a foreshadowing of his own unease with debt.

Washington also brought some book learning to his descriptions. He referenced Griffith Hughes’s 1750 The Natural History of Barbados and matched his own descriptions of plants to those of Reverend Hughes. When and where Washington saw the book is unclear. A copy did not end up in his library, but there may have been one at the Fairfaxes’. It is also possible that he had a copy (or bought a copy) on the island itself. However he laid his hands on Hughes’s work, it is one of the earliest examples we have of Washington employing reading in this fashion.

The brothers settled into a simple one-story rented house which sat on a rise of land a short distance east of Bridgetown. For the cost of 15 Pounds a month paid to an officer of the garrison, they had the run of the place—but they had to pay for their own liquor and laundry. The home was close to the stone coral fort at Needham’s point and close to the garrison’s parade ground. It also afforded a superb view of Carlisle Bay with its ships riding at anchor. This home is now restored to an eighteenth-century appearance and serves as a museum dedicated to the Washingtons’ time on the island. The home is larger than it was then and has had a second story added to it, but the feel is there. The area around it is completely changed as well. The commanding view is blocked by trees and a new building cut directly into the limestone hillside. The garrison has changed considerably too. What began as useful flat near Needham’s Point grew in the nineteenth-century into an expansive military complex ringing a large turf race course. Today it all is the home of schools, government buildings, the Barbados Historical Society and museum, and the Barbados Defense Forces who, by the way, have a legal monopoly on the wearing of camouflage on the island. Colonial Williamsburg conducted excavations at the home in 1999 and 2001. These mainly concentrated on the steep ravine to the east of the home—a logical place for centuries’ worth of trash to accumulate. Virginia students still return here to do some digging in the ravine to this day. The artifact assemblages though cover a large swath of time, and apart from some very familiar 1740s and 50s white salt glazed stoneware plate, nothing has emerged dating with any precision to the years of the Washington visit—nor is anything much likely to. Nevertheless, the lower parts of the house—and especially its cellar with its hewn stone and wooden beams—are good links to the eighteenth century.

While the purpose of the trip was largely medical, the Washingtons did a considerable amount of socializing with the local gentry. Their main contact on the island was Gedney Clarke, a player in the local commerce and governance as well as being Lawrence’s wife Anne’s stepmother’s brother (head spinning as that connection seems to us, eighteenth-century English families were pretty used to these extended networks of kin by blood or marriage).

Clarke had a thriving trade with William Fairfax and sent not only sugar and rum to the Potomac, but also procured enslaved people and goods for the Fairfaxes and other members of their extended commercial family—including both Lawrence and George. Clarke opened society’s doors, and with his aid Washington toured fortifications, dined with several prominent families (sometimes with their daughters deliberately placed front and center), attended the theatre, went to church, and rode into the countryside when he could. It is not clear just how far northward Washington actually ventured. His descriptions best match the rising hills of the south, and nowhere did he mentioning the rather astounding natural features of the north. He did nevertheless refer to people who at least had land there even if Washington never made it that far above the Bridgetown area.

Washington clearly was matching what he saw on the island against what he knew at home. “The ladys generally are very agreeable” he wrote, but also felt that they were prone to “affect the Negro style” perhaps in speech and manner—something the young Virginian saw as a liability compared to the women he knew back home. (Toner, 61). This racially inflected haughtiness was no doubt one of the reasons that he did not return home with a Barbadian bride or a prospect in mind. He noted the level of militia service and how men were apportioned in some detail, and he also discussed the island’s defenses noting that “they have large Intrenchments cast up wherever its possible for an enemy to land.” (Toner, 62). I find it very interesting that Washington paired concerns about race and fortifications in his journal—something that I will be discussing in the upcoming book’s Barbados chapter.

Clarke—or rather, someone in the Clarke household—was responsible for the most enduring outcome of the Barbados trip—George’s bout with small pox. The Washingtons knew that someone either at the Clarke plantation house or the in-town house had the disease, but they risked a dinner visit nonetheless. Once the illness had passed Washington could record in the diary that on November 17th, he “was strongly attacked with the small pox.” (Toner, 53). As these things went, it was on the mild side and obviously could have gone far worse. But that would have meant nothing to a young man sweating out a renowned deadly fever far from home and attended by caring, though ultimately unfamiliar people.

He spent most of November in bed—the diary is understandably silent. By December 12th he was recovered enough to visit the Clarkes in Bridgetown and thank them for their care and visits during his illness. The consequences of Washington’s smallpox are difficult to pin down. There are those who like to say that that fevered island month inoculated George against the disease, and thus ensured that he would not die of it before, or even during the Revolution. That line of reasoning’s implications are clear: a small amount well-timed body fluid contact preserved Our Washington and in so doing secured the fate of the Republic. There are a lot of “ifs” in that charming premise, but one can understand how such a view could take root. The other often-cited consequence was that the fever rendered Washington incapable fathering children. This outcome is the opposite of the former outcome. In the former, Washington is saved to be the Father of the Country, whereas in the later he is denied the ability to be a father. And of course there is a relationship between the two outcomes. The challenge here is the uncertain relationship between small pox and male sterility. The simplest version of this relationship is that there is none—small pox does not cause sterility. The fever itself though can do permanent damage and other opportunistic illnesses can do their horrid work while a body’s defenses are down. The answer though is that we cannot say with any real certainty that the lack of direct line little Washingtons was because of that poorly timed dinner at the Clarkes’s.

As this rather long entry shows, I have quite a bit to say about Washington and Barbados—here I just spun out a few of the themes I am working with. And I have not even touched yet on Washington memory on the island long after the famed visit. A few important take aways though are the value of the Barbados Diary as an early and quite revealing Washington foray into the world of words. Another is the chance to see the Virginian mind (some may say gaze) examining a place similar enough to grant purchase, but alien enough to captivate. Still another is what we see of the island itself. The Barbados trip is usually a quick moment in most Washington literature. I am glad I am giving it a bit more page space than is usual.

Rebekah Munson is a graduate student at the University of South Florida with a major focus on Medieval Sicily and a minor focus on Digital Bioarchaeology. During her time in graduate school she has worked on numerous digital archaeological projects and currently is the editorial assistant for

Rebekah Munson is a graduate student at the University of South Florida with a major focus on Medieval Sicily and a minor focus on Digital Bioarchaeology. During her time in graduate school she has worked on numerous digital archaeological projects and currently is the editorial assistant for  The western border of the Washington land Lamkin surveyed was the road he called the Road to the Burnt House–it is the backwards L I have highlighted in this close up photo. The ultimate destination and name of that road is a question in and of itself, but for now, let’s focus on the spur that breaks off to its south–also highlighted here. Lamkin called this eastbound spur the Road to Washington’s Mill. Indeed, there was a mill at the head of Pope’s Creek for ages–the remains of its 20c iteration are still there to be seen. The area is now called Potomac Mills–not be confused with the giant mall on I-95 near DC. Right where Lamkin has written “Washington’s” there is another road forking with a spur headed back westward–making for a sort of backwards Z of a road.

The western border of the Washington land Lamkin surveyed was the road he called the Road to the Burnt House–it is the backwards L I have highlighted in this close up photo. The ultimate destination and name of that road is a question in and of itself, but for now, let’s focus on the spur that breaks off to its south–also highlighted here. Lamkin called this eastbound spur the Road to Washington’s Mill. Indeed, there was a mill at the head of Pope’s Creek for ages–the remains of its 20c iteration are still there to be seen. The area is now called Potomac Mills–not be confused with the giant mall on I-95 near DC. Right where Lamkin has written “Washington’s” there is another road forking with a spur headed back westward–making for a sort of backwards Z of a road.

This NPS commissioned painting is a fine representation of the fanciful landscape as imagined by the 1920s folks, here painted with newer understandings of outbuildings layered onto it. It is not a bad vision of an 18c Virginia plantation–it’s just that it is composed of made up parts. No such plantation existed here. The painting shows the fanciful 1920s Memorial House Museum as the Washington home. It was not. In fact, there was very little actual research that went into its building. It was a vanity project by an autonomous group of commemorators and the home looks like a cross between Gunston Hall and Twifford which was the home of the main backer’s grandmother.

This NPS commissioned painting is a fine representation of the fanciful landscape as imagined by the 1920s folks, here painted with newer understandings of outbuildings layered onto it. It is not a bad vision of an 18c Virginia plantation–it’s just that it is composed of made up parts. No such plantation existed here. The painting shows the fanciful 1920s Memorial House Museum as the Washington home. It was not. In fact, there was very little actual research that went into its building. It was a vanity project by an autonomous group of commemorators and the home looks like a cross between Gunston Hall and Twifford which was the home of the main backer’s grandmother.

As NPS historian John Hennessy points out, there is not much else to lock in the story of the block. The local memory though is pretty strong, and needs to be given due weight—indeed, it has. There is a rival story that the block was a stepping stone for carriages and horses, but we can just push that aside since there is nothing about that role that would prevent the block from serving as an auction block as well at another time.

As NPS historian John Hennessy points out, there is not much else to lock in the story of the block. The local memory though is pretty strong, and needs to be given due weight—indeed, it has. There is a rival story that the block was a stepping stone for carriages and horses, but we can just push that aside since there is nothing about that role that would prevent the block from serving as an auction block as well at another time.

It seems though that the order was almost literally a day late and a dollar short. Last year, developer Mike Adams purchased the property from PNC Financial Services and floated a few plans for the building and lot. The latest is to turn the bank building into a restaurant and offices and put seven town houses in the lot. The former seems like a reasonable low-impact use of a historical structure, the later through still threatens to overwhelm the lot and over shadow the old building. The project began with the removal of the drive-through, but at the last moment the city’s Architectural Review Board–frequently a site of preservation battles–has thrown cold water on Adams’s plans. He has replied with a suit, and the city returned fire on Monday by sending over the cops to enforce the ban. From what I saw though, there was not much left to cry over.

It seems though that the order was almost literally a day late and a dollar short. Last year, developer Mike Adams purchased the property from PNC Financial Services and floated a few plans for the building and lot. The latest is to turn the bank building into a restaurant and offices and put seven town houses in the lot. The former seems like a reasonable low-impact use of a historical structure, the later through still threatens to overwhelm the lot and over shadow the old building. The project began with the removal of the drive-through, but at the last moment the city’s Architectural Review Board–frequently a site of preservation battles–has thrown cold water on Adams’s plans. He has replied with a suit, and the city returned fire on Monday by sending over the cops to enforce the ban. From what I saw though, there was not much left to cry over.

Recent Comments