Lauren Piccinini is a Master’s student with the University of South Florida. Her area of concentration is American History with a specialization regarding American Prisoners of War.

Andersonville Prisoner of War Camp and Covid-19

As the world slowly turned to a grinding halt due to the rapid spread of 2019-nCoV, commonly known as Coronavirus, the historical community began racing to find a way to continue “front-line education.” In this defining and unprecedented time, the world must find a way to move forward without actually moving, thus social media has stepped into the forefront as a source of delivery for museums, national parks, and educational institutions. Utilizing this technology and platform, historical institutions have been able to reach a whole new audience during this time of quarantine and social distancing.

One such institution that has embraced this way of meeting with the community is the National Prison of War Museum, which sits on the remains of the Andersonville Prisoner of War camp. Andersonville Camp, formerly known as Camp Sumter, was built as a Union Prisoner of War camp during the American Civil War and was designed to hold roughly 10,000 prisoners.  When it opened to receive prisoners in April, 1984, the Confederacy was ill-equipped to deal with the Union prisoner population. This is clearly evident as the camp was not fully completed when the first prisoners arrived. Nonetheless, the camp continued to accept prisoners and by August, 1864, the population within the camp swelled to over 33,000 men. As a direct result, the conditions within the camp deteriorated and mortality ranks surged, to almost 13,000 Union soldiers. The leading causes of death within the camp were chronic diarrhea, dysentery, and scurvy. While Andersonville was only in operation for fourteen months, it received over 45,000 soldiers and is notorious for being the largest and most deadly Confederate Prisoner of War camp. [1]

When it opened to receive prisoners in April, 1984, the Confederacy was ill-equipped to deal with the Union prisoner population. This is clearly evident as the camp was not fully completed when the first prisoners arrived. Nonetheless, the camp continued to accept prisoners and by August, 1864, the population within the camp swelled to over 33,000 men. As a direct result, the conditions within the camp deteriorated and mortality ranks surged, to almost 13,000 Union soldiers. The leading causes of death within the camp were chronic diarrhea, dysentery, and scurvy. While Andersonville was only in operation for fourteen months, it received over 45,000 soldiers and is notorious for being the largest and most deadly Confederate Prisoner of War camp. [1]

Following the American Civil War, Clara Barton and Dorence Atwater, a former prisoner, returned to the site in order to categorize and rebury all of the deceased men. Since that time, the camp and the burial grounds have fallen into the hands of the National Park system. In recent years, the camp dedicated a museum on the grounds to inform the public on the perils of being a prisoner of war and expanded the scholarship beyond the American Civil War. Annually, the camp hosts Living History weekend, night tours, and educational seminars that are designed to engage the average citizen into the topic of prisoners of war.

When the novel Coronavirus began to spread in the United States, the park took notice and by March 18, 2020, the camp made the decision to close the museum for the safety and wellbeing of their guests, volunteers, and employees.  On March 24, 2020, the camp, having been influenced by the Center for Disease Control and the state of Georgia, closed the park grounds to visitors and they have suspended all military honors during burials at the National Cemetery, which is the burial ground that Atwater and Barton established and sits on the camp grounds. In an effort to remain connected to the individuals who intended to attend a workshop or visit the museum, the park service has engaged the public using livestreaming capabilities on social media platforms, such as Facebook or Instagram.

On March 24, 2020, the camp, having been influenced by the Center for Disease Control and the state of Georgia, closed the park grounds to visitors and they have suspended all military honors during burials at the National Cemetery, which is the burial ground that Atwater and Barton established and sits on the camp grounds. In an effort to remain connected to the individuals who intended to attend a workshop or visit the museum, the park service has engaged the public using livestreaming capabilities on social media platforms, such as Facebook or Instagram.

On the morning of March 28, 2020, Ranger J with the National Park Service at Andersonville greeted thousands of people who were interested in taking a virtual tour of Andersonville. As I sat comfortably on my couch, I saw people checking in from places near and far: Florida, Kentucky, Ohio, New York, Illinois, Utah, Iowa, South Dakota, England (UK), Switzerland, and Afghanistan. While geography certainly was not a commonality with the viewers, the topic of Andersonville prison site certainly connected all of us. For the next 40 minutes, Ranger J introduced an unimaginable amount of people to the history of the camp, the players involved with the camp, and answered questioned posed by her viewers. By midday on March 29, 2020, Ranger J’s livestream had been viewed over 17,000 times. I believe that it is safe to assume that this is largest amount of people who have “visited” the camp in a single morning. Due to the overwhelming popularity, the camp has decided to dedicate Saturday mornings to “Social Saturdays,” with the next stroll occurring on April 4, 2020. This upcoming stream will focus on the burial grounds and the history associated with those interned.[2]

As the world changes, historical institutions have to adjust in order to deliver their content to a new population. During these uncertain times, it appears that the use of livestreaming tours has generated new life into old topics. While quarantining seems boring and lifeless, it is an excellent time to learn something new, of which Andersonville National Park has delivered. Make sure to tune in this, and all upcoming, Saturdays for information on the site, the prisoners who suffered and those who were responsible.

[1] Information on Andersonville POW camp obtained from: McPherson, James, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1988)

[2] Information on Andersonville National Park obtained from: “Causes of Death” Available from https://www.nps.gov/ande/learn/historyculture/causesofdeath.htm, “Alerts & Conditions” Available from https://www.nps.gov/ande/planyourvisit/conditions.htm & “Camp Sumter/Andersonville Prison” Available from https://www.nps.gov/ande/learn/historyculture/camp_sumter.htm

Cheryl Burstein is pursing a Masters degree in history at the University of South Florida.

Cheryl Burstein is pursing a Masters degree in history at the University of South Florida. Alexander Obermueller currently works on his Master’s thesis on the Raiford prison uprising of 1971. Before coming to USF he graduated from the University of Vienna and worked on a

Alexander Obermueller currently works on his Master’s thesis on the Raiford prison uprising of 1971. Before coming to USF he graduated from the University of Vienna and worked on a  Josh Sanders is a M.A. student at the University of South Florida. He majors in 20th Century American history with a minor in 19th Century American history.

Josh Sanders is a M.A. student at the University of South Florida. He majors in 20th Century American history with a minor in 19th Century American history. Scott Miller is a PhD student at the University of South Florida. His area of concentration is 20th Century American history with a focus on the Cold War.

Scott Miller is a PhD student at the University of South Florida. His area of concentration is 20th Century American history with a focus on the Cold War. Rebekah Munson is a graduate student at the University of South Florida with a major focus on Medieval Sicily and a minor focus on Digital Bioarchaeology. During her time in graduate school she has worked on numerous digital archaeological projects and currently is the editorial assistant for

Rebekah Munson is a graduate student at the University of South Florida with a major focus on Medieval Sicily and a minor focus on Digital Bioarchaeology. During her time in graduate school she has worked on numerous digital archaeological projects and currently is the editorial assistant for  Alexander Obermueller currently works on his Master’s thesis on the Raiford prison uprising of 1971. Before coming to USF he graduated from the University of Vienna and worked on a

Alexander Obermueller currently works on his Master’s thesis on the Raiford prison uprising of 1971. Before coming to USF he graduated from the University of Vienna and worked on a  By using this poster, the social media staff shows flexibility and creativity connecting past and current events to call on the public to “stay save and at home.” The hash tags #museumfromhome and #closedbutactive are also frequently used. Hygiene makes another appearance in a post about the renowned Viennese architect Otto Wagner. By stressing Wagner’s focus on comfort and hygiene as pillars of truly modern architecture, the long history of concern for hygiene is once more displayed.

By using this poster, the social media staff shows flexibility and creativity connecting past and current events to call on the public to “stay save and at home.” The hash tags #museumfromhome and #closedbutactive are also frequently used. Hygiene makes another appearance in a post about the renowned Viennese architect Otto Wagner. By stressing Wagner’s focus on comfort and hygiene as pillars of truly modern architecture, the long history of concern for hygiene is once more displayed. Attuned to the more casual tone on Instagram, staff posted a picture that lauds well-practiced social distancing: Only one person sits on each bench in the park outside of the Wien Museum. Again, the connection between the crisis and new social practices, namely social distancing, is tied to the museum by using a picture of the near vicinity.

Attuned to the more casual tone on Instagram, staff posted a picture that lauds well-practiced social distancing: Only one person sits on each bench in the park outside of the Wien Museum. Again, the connection between the crisis and new social practices, namely social distancing, is tied to the museum by using a picture of the near vicinity. The new reality forces many of us to be confined to our homes by shelter in place ordinances all across the world. For those lucky enough to continue their jobs at home and not being fired, this change often results in a more relaxed working experience. Fitness and recipe challenges pop up all over the Internet to make the prolonged indoor stay bearable. Especially those employed in secure jobs and equipped with financial savings embrace the new homemaking or Biedermeier movement and embark on proper baking sprees. Being on lock down also confronts people with their living space and the Wien Museum jumps that train by referencing museums’ focus on and exhibitions about the home under the hash tag #atmuseumsanywhere. By sharing a picture of author Franz Grillparzer’s home, the social media team acknowledges the current, (en)forced fixation on the home.

The new reality forces many of us to be confined to our homes by shelter in place ordinances all across the world. For those lucky enough to continue their jobs at home and not being fired, this change often results in a more relaxed working experience. Fitness and recipe challenges pop up all over the Internet to make the prolonged indoor stay bearable. Especially those employed in secure jobs and equipped with financial savings embrace the new homemaking or Biedermeier movement and embark on proper baking sprees. Being on lock down also confronts people with their living space and the Wien Museum jumps that train by referencing museums’ focus on and exhibitions about the home under the hash tag #atmuseumsanywhere. By sharing a picture of author Franz Grillparzer’s home, the social media team acknowledges the current, (en)forced fixation on the home.

When it opened to receive prisoners in April, 1984, the Confederacy was ill-equipped to deal with the Union prisoner population. This is clearly evident as the camp was not fully completed when the first prisoners arrived. Nonetheless, the camp continued to accept prisoners and by August, 1864, the population within the camp swelled to over 33,000 men. As a direct result, the conditions within the camp deteriorated and mortality ranks surged, to almost 13,000 Union soldiers. The leading causes of death within the camp were chronic diarrhea, dysentery, and scurvy. While Andersonville was only in operation for fourteen months, it received over 45,000 soldiers and is notorious for being the largest and most deadly Confederate Prisoner of War camp.

When it opened to receive prisoners in April, 1984, the Confederacy was ill-equipped to deal with the Union prisoner population. This is clearly evident as the camp was not fully completed when the first prisoners arrived. Nonetheless, the camp continued to accept prisoners and by August, 1864, the population within the camp swelled to over 33,000 men. As a direct result, the conditions within the camp deteriorated and mortality ranks surged, to almost 13,000 Union soldiers. The leading causes of death within the camp were chronic diarrhea, dysentery, and scurvy. While Andersonville was only in operation for fourteen months, it received over 45,000 soldiers and is notorious for being the largest and most deadly Confederate Prisoner of War camp.  On March 24, 2020, the camp, having been influenced by the Center for Disease Control and the state of Georgia, closed the park grounds to visitors and they have suspended all military honors during burials at the National Cemetery, which is the burial ground that Atwater and Barton established and sits on the camp grounds. In an effort to remain connected to the individuals who intended to attend a workshop or visit the museum, the park service has engaged the public using livestreaming capabilities on social media platforms, such as Facebook or Instagram.

On March 24, 2020, the camp, having been influenced by the Center for Disease Control and the state of Georgia, closed the park grounds to visitors and they have suspended all military honors during burials at the National Cemetery, which is the burial ground that Atwater and Barton established and sits on the camp grounds. In an effort to remain connected to the individuals who intended to attend a workshop or visit the museum, the park service has engaged the public using livestreaming capabilities on social media platforms, such as Facebook or Instagram. Alexander Obermueller currently works on his Master’s thesis on the Raiford prison uprising of 1971. Before coming to USF he graduated from the University of Vienna and worked on a

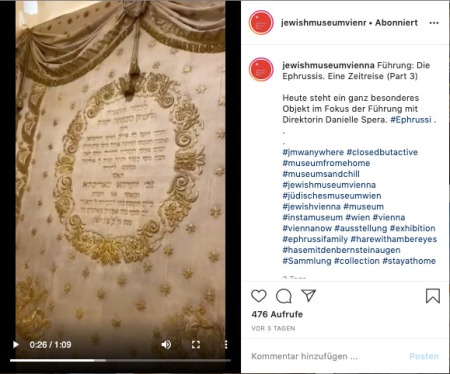

Alexander Obermueller currently works on his Master’s thesis on the Raiford prison uprising of 1971. Before coming to USF he graduated from the University of Vienna and worked on a  Danielle Spera guides virtual visitors through the current Ephrussi exhibition and narrates what visitors usually experience on their own. The hash tags #digitalmuseum and #museumfromhome signify the mediated museum experience. Another hash tag #jmwanywhere stresses the possibility to visit the Jewish Museum Vienna from anywhere. Additionally the social media team started using #stayathome a call on the community to protect those who are vulnerable and stay away from an institution that usually aims at attracting visitors.

Danielle Spera guides virtual visitors through the current Ephrussi exhibition and narrates what visitors usually experience on their own. The hash tags #digitalmuseum and #museumfromhome signify the mediated museum experience. Another hash tag #jmwanywhere stresses the possibility to visit the Jewish Museum Vienna from anywhere. Additionally the social media team started using #stayathome a call on the community to protect those who are vulnerable and stay away from an institution that usually aims at attracting visitors. The Jewish Museum Vienna’s permanent exhibition is accessible via Google Arts & Culture and on the current exhibition one can find an image video produced for the kick off of the exhibit, yet the current situation calls for improvisation. Virtual visitors profit from a rather exclusive format – it rarely happens that a museum director herself guides you through a tour.

The Jewish Museum Vienna’s permanent exhibition is accessible via Google Arts & Culture and on the current exhibition one can find an image video produced for the kick off of the exhibit, yet the current situation calls for improvisation. Virtual visitors profit from a rather exclusive format – it rarely happens that a museum director herself guides you through a tour. Corona not only presents a challenge to institutions as a whole but also forces museum professionals to step into the spot light or get engaged with social media. Whereas the trained journalist Danielle Spera performs her tours eloquently other museum staff understandably struggles to adjust to the unfamiliar and challenging setting.

Corona not only presents a challenge to institutions as a whole but also forces museum professionals to step into the spot light or get engaged with social media. Whereas the trained journalist Danielle Spera performs her tours eloquently other museum staff understandably struggles to adjust to the unfamiliar and challenging setting. My graduate Public History seminar this semester has been driven online thanks to CV19. This of course has barred the possibility of people coming up with new interesting projects. A few students already have something clever going on, so they are taken care of and are burrowing away. But the rest of us decided that the best thing to do was focus on the web and explore how public historical sites, museums, and other related entities are coping with this pandemic. The plan is to share their findings here. So, over the next few weeks I will be posting students’ work as we take a look at how public history reacts and responds.

My graduate Public History seminar this semester has been driven online thanks to CV19. This of course has barred the possibility of people coming up with new interesting projects. A few students already have something clever going on, so they are taken care of and are burrowing away. But the rest of us decided that the best thing to do was focus on the web and explore how public historical sites, museums, and other related entities are coping with this pandemic. The plan is to share their findings here. So, over the next few weeks I will be posting students’ work as we take a look at how public history reacts and responds.

Recent Comments