In the field of history, all doctoral programs are built on the intentions of the first mitzvah in the Torah — Pru Uvru — be fruitful and multiply. The idea is to produce the next generation of faculty to take off when we all, I dunno, die, I guess. If the Talmud’s Sages were to rule on a doctoral program they might conclude that a faculty member has fulfilled this professional mitzvah once they have hooded one student—or better yet, when that one student has a tenure tack job. In fact, many faculty reproduce more like Ghengis Khan than like a pair of well-to-do physicians in today’s Frankfurt or San Francisco. My dissertation director oversaw somewhere in the range of 75 newly minted PhDs in his long career. Virtually all of them hatched into good academic jobs. Few today though could claim such professional fecundity—the world has changed so much in such a short time. Forty years of budget cutting, maligning, and beast starving has turned what was once a somewhat prestigious pathway to modest middle class comfort into a medieval cast system where all rewards accrue to a few while armies of overqualified contingently employed souls toil trapped in a dead end that makes the title “professor” a painful insult.

dissertation director oversaw somewhere in the range of 75 newly minted PhDs in his long career. Virtually all of them hatched into good academic jobs. Few today though could claim such professional fecundity—the world has changed so much in such a short time. Forty years of budget cutting, maligning, and beast starving has turned what was once a somewhat prestigious pathway to modest middle class comfort into a medieval cast system where all rewards accrue to a few while armies of overqualified contingently employed souls toil trapped in a dead end that makes the title “professor” a painful insult.

Each year people like me have to sit with ambitious, intelligent, motivated budding scholars and are called upon to smash to pieces their dreams of an academic career—no, I cannot fulfill the mitzvah of professional Pru Uvru on your behalf. Larry Cebula put it more bluntly in his noted 2011 post “No, You Cannot be a Professor.”

While I share much of Larry’s outlook, I am not totally on board—and that is why I wanted to write this here so that I don’t have to do it over and over each cycle. Each year I have more or less the same exchanges about how to get into a program and what to expect. I am restricting myself here to the front end–this is not meant to be a post about the job market–but obviously the market and admissions blend. My own experience with students denies me the ability to say that they cannot be professors—I know for a fact that they can be–real ones, tenure track and all. But—and this is a big one—they have to be pretty exceptional. By that I mean that there is a magic combination of ambition, stick-to-it-ness, and raw talent that also needs to fuse with some other sort of off-screen alchemy—skills, background, experience, and so on—that can make one stand out. On top of that, one had better be ready to publish, attend, and self-promote from the start. Long gone are the days when one could wait out an economic storm by hiding in grad school.

These days, that is like hiding from the rain by running into the nearest house. But the house is inhabited by a human flesh eating Minotaur, and is a working abattoir with massive sharp blades spinning and skittering every which way, and is on fire. All told, you are better off staying in the rain. So, take a deep look into your soul dear applicant and ask yourself the hard questions. What did you write in your Statement of Purpose? Did you share your life-long love of history? Did that begin when your family visited historical sites? Did [fill in topic here] fascinate you even from childhood? If the answers here are yes, then thank you for playing—Doris will meet you at the door with some lovely parting gifts (who am I kidding? As if we would have the budget for parting gifts! We don’t even have the money for cookies in a monthly meetings!).

Lesson One: Grad School is a Job. You are asking the state or a private institution to fund you to be a student—that funding comes in the form of small stipends and in the form of tuition waivers. If you are not in the running for funded education, or have been accepted to a program that wants you to pay for the privilege, well, I see Doris coming with your parting gifts.

- http://www.wonderlist.com

Past performance is the only visible (albeit imperfect) measure of future success. What have you published thus far (I had a history magazine article under review when I applied)? What projects have you worked on that bear on what you intend to do with the school’s money? Conferences presented at so far? As the old saying goes—dress for the gig you want, not the one you have. So, show us how you have been dressing up as a working scholar already. A good statement of purpose needs to read more like a research grant than a personal bio—since from the school’s perspective you are asking for its money. So unless you can muster that sort of letter, save yourself the trouble. Doris…..?

Lesson Two: Doctoral Study is Relational. As a doctoral candidate you will be building, ideally, a fairly close and long lasting relationship with another human being—preferably one whose work you find influential. That is not to say that you need to be a clone, but the mentor relationship is the core of the experience. It is your mentor’s name you will cash in on at first and it is their contacts list that will constitute your first line of professional allies. In most cases, your first opportunities will come from their projects, and of course you will spend years learning to write to their standard. It is surprising how many people apply without even so much as a mention of the name of the person their interests suggest they will be working with. Astounding! If that is you, you have failed Test One—and it is a biggie.

You are asking the school to pay you to do research, and yet you failed to even research the department enough to convincingly talk about how Professor Magic has shaped your thinking on Your Chosen Topic, and how she/he is an ideal match for your work. On top of that, what sorts of university resources, ancillary programs, library collections, and so on are vital to your success in Your Chosen Topic? If the best you can muster for a reason to attend a program is proximity, well, Doris is ready with your basket. There is also a secret punch line here. Grad school is not undergraduate education, and admissions do not work the same way. Sure, past grades and all that are important. But more important is if Professor Magic wants to take you on as a student! Yes, that’s right, this is a buyer’s market and the merit of a student’s interests are central to admissions. It is not an issue of snobbery—it is one of workload and realistic expectations. Will Professor Magic be on leave? Does she/he have too many students now or a book deadline they are pushing? Is what you want to do close enough to Professor Magic’s work that they feel they can help you in the first place? If you have not researched these questions before you apply, and even perhaps met with Professor Magic for coffee to talk this all over, then Doris is tapping you on the shoulder.

Lesson Three: History Programs Train You to Be a Historian. Not Much Else. No Plan B (formerly known as Plan B) has been a big topic in virtually every academic historical society. Departments all over the land are soul searching and head scratching to see what else new PhDs can do other than being professors. In truth, I don’t think the news is great here. People trained to be professors and who have been successful in that role are not the best positioned to teach you to work in business, say for example. Ask yourself this question: what skills can I learn in a doctoral program that I cannot gain in some other more time and cost-effective way? In most cases, there answer is not many. No matter how much we fret about it, doctoral training is still Pru Uvru—we are still training people to be professors. These days that means much more attention to digital media than a decade ago, and that is good news. But the computer training one might get in a history department is a pale shadow of what you might get elsewhere or even on your own. The challenge of digital media to the way history is practiced is really one of disrupted information delivery systems and author credentialing. There is not a mini job boom in digital history outside of a few job listings—at least not one outside academe large enough to set a career upon, and probably not one for which you need a doctorate. The centerpiece of doctoral education is still the dissertation—and that remains a book- length written work resting on original research. We are approaching a time where it may be commonplace for dissertations to be digital projects, and some of those projects might be patentable software or marketable digital projects.

I for one welcome that—and I am working with students who see the world that way. But—if such a project is to be successful, it will rely on coding skills and computer knowledge gained well before doctoral study began. Class work will be working towards prepping candidates for an average of three comprehensive exams in various fields each resting on a reading list of between 60 and 100 books. There is not a lot of time to become masterful at coding in that preparation period, and so far, few in any programs have been willing to throw away the old models to make room for something new. But then again, if you are applying I am sure you have done all the research to understand upfront just what the program will be asking of you….! Is there an ongoing digital program or project at your chosen school that is central to what you propose to do? Again, I am sure you will have noted that in your researching the program. If not, Doris is waiting.

Lesson Four: Just Because You Like it Does Not Make it a Field. Sorry boys, WWII is not an academic field. Modern Europe is, but not a war—no matter how much TV seduces you over and over with endless press-molded documentaries. From the very beginning you need to be defining yourself and your interests in terms the field understands. This is a guild, and you are a supplicant asking the guild to dispense resources to recognize you as one of its own. It is a quirky guild—we love nothing more than a member who can shake things up. But it is also a classic case of needing to know the rules before you can break them. If you cannot define yourself in terms the guild recognizes, then it will have a hard time seeing you as a prospect.

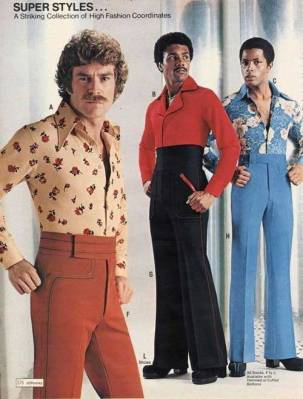

One way to get in the swing is to look at the current job adds posted by H-net and the AHA. But of course there is a catch. The discipline is super fashion conscious. I won’t say that we mindlessly chase shiny objects, but since we are always looking to up turn the world, or to have our worlds up turned, we are sensitive to new ideas—and pretty into them. So even though it pays to know what is hot at the moment, know that while also knowing that there will be something else hot in a few years or even less. And nothing is less hot than last year’s fashion. The ideal topic is one that seems cutting edge at the moment of proposal, but has the elasticity to morph into the new cutting edge six or seven years from now. That is one heck of a challenge—but Doris is waiting if it is too much.

Know this though. None of us on this side of the line are happy about the current situation. We want to retire, eventually, and at our retirement dinners we want to be surrounded with friends and family—and especially by the many students whose careers we helped start. Setting a promising student’s career in motion and watching them mature into a confused, overloaded, and bitter faculty member is one of life’s great pleasures. If we had our druthers, programs would be fully funded and there would be scads of creative opportunities—we could get back to pretending that academe was a meritocracy. Ah, the old days! But others have set us all on this path and we are just along the dismal ride. So am I saying Nevermore? Not really. What I am saying is tread softly and advisedly in the minefield, and put yourself through the wringer before you put yourself through the wringer. But, you should probably just not put yourself through the wringer. Here comes Doris with some nice gifts and nice life outside academe.

Scott Miller is a PhD student at the University of South Florida. His area of concentration is 20th Century American history with a focus on the Cold War.

Scott Miller is a PhD student at the University of South Florida. His area of concentration is 20th Century American history with a focus on the Cold War.

dissertation director oversaw somewhere in the range of 75 newly minted PhDs in his long career. Virtually all of them hatched into good academic jobs. Few today though could claim such professional fecundity—the world has changed so much in such a short time. Forty years of budget cutting, maligning, and beast starving has turned what was once a somewhat prestigious pathway to modest middle class comfort into a medieval cast system where all rewards accrue to a few while armies of overqualified contingently employed souls toil trapped in a dead end that makes the title “professor” a painful insult.

dissertation director oversaw somewhere in the range of 75 newly minted PhDs in his long career. Virtually all of them hatched into good academic jobs. Few today though could claim such professional fecundity—the world has changed so much in such a short time. Forty years of budget cutting, maligning, and beast starving has turned what was once a somewhat prestigious pathway to modest middle class comfort into a medieval cast system where all rewards accrue to a few while armies of overqualified contingently employed souls toil trapped in a dead end that makes the title “professor” a painful insult.

Recent Comments