We need some background. George Washington’s birthplace is in Westmoreland County, Virginia. It is just off of Route 3 about 40 miles east of Fredericksburg. If you drive out to visit there you can also swing by Stratford Hall a few miles farther east and see one of the most remarkable eighteenth-century Virginia homes. Washington’s Birthplace–some times called Pope’s Creek, other times called by its mid-18c name Wakefield–is owned and run by the National Park Service. The site’s NPS name is GeWa (first two letters of a site’s first two names), and I have gotten pretty used to that name. But GeWa is not an easy site to interpret to visitors. There was not much left of the old Washington homestead above ground by the start of nineteenth century. The location of the home—the Washington birth home—that so many have wanted to find has been a mystery since then. Everything built that is visible today is new–and error riddled. For a deeper background on the colonial history of the site and how the park has reported it, take a look at this Cultural Landscape Inventory. It is a good survey of the land ownership history and some of the challenges. It also embeds some of the assumptions we are now challenging.

This is Benson Lossing’s etching of the stone Parke Custis left at the site. Lossing never saw the stone.

In 1815 George Washington Parke Custis and friends placed a commemorative stone where they thought the home had been, but they relied on the memory of others to locate the site. Since then the focus has been on where that stone had been. Even in the 1920s as the nation was getting ready for the Washington birth bicentennial, debate still focused on a chain of memory used to locate the lost stone. Independent evidence—like archaeology—was made to fit with stories and privileged memories rather receive its just due as an authoritative and independent stream of information. The park is now working to correct the confused mix of stories that have held sway for decades, and I am glad to be helping.

This NPS commissioned painting is a fine representation of the fanciful landscape as imagined by the 1920s folks, here painted with newer understandings of outbuildings layered onto it. It is not a bad vision of an 18c Virginia plantation–it’s just that it is composed of made up parts. No such plantation existed here. The painting shows the fanciful 1920s Memorial House Museum as the Washington home. It was not. In fact, there was very little actual research that went into its building. It was a vanity project by an autonomous group of commemorators and the home looks like a cross between Gunston Hall and Twifford which was the home of the main backer’s grandmother.

This NPS commissioned painting is a fine representation of the fanciful landscape as imagined by the 1920s folks, here painted with newer understandings of outbuildings layered onto it. It is not a bad vision of an 18c Virginia plantation–it’s just that it is composed of made up parts. No such plantation existed here. The painting shows the fanciful 1920s Memorial House Museum as the Washington home. It was not. In fact, there was very little actual research that went into its building. It was a vanity project by an autonomous group of commemorators and the home looks like a cross between Gunston Hall and Twifford which was the home of the main backer’s grandmother.

This is a Historic American Building Survey photo of Twifford in King George County, Virginia.

Not only that, but they sat their brick version of Twifford atop the remains of a curious outbuilding—remains which were destroyed in the building process. The rest of landscape is more imagination than anything else. We saw the same thing at Ferry Farm where an iconic set of errors were reinscribed with each new rendering giving new life over and over to old error. Nevertheless, this painting captures what visitors to the site see (more or less) and what rangers work so hard to clarify. It is a difficult task since so much of the available information and art is working against their efforts to share a better understanding. The little white outline on the right has been called Building X. That is the set of brick foundation features—excavated in 1930 and 1936 and which we re examined in 2013. These have been labeled the real Washington birth home, but that is a dubious claim at best. The whole site is a work in progress.

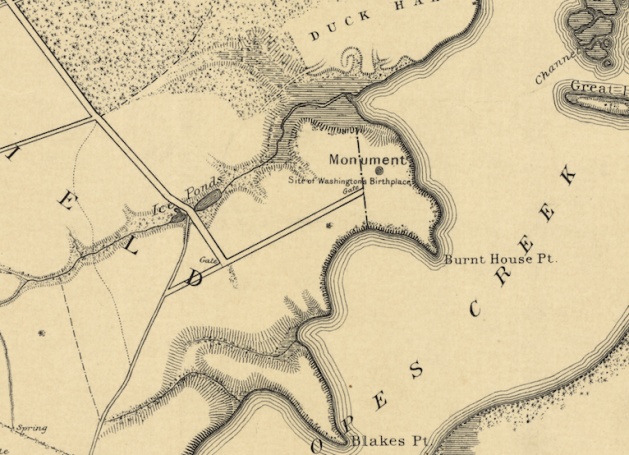

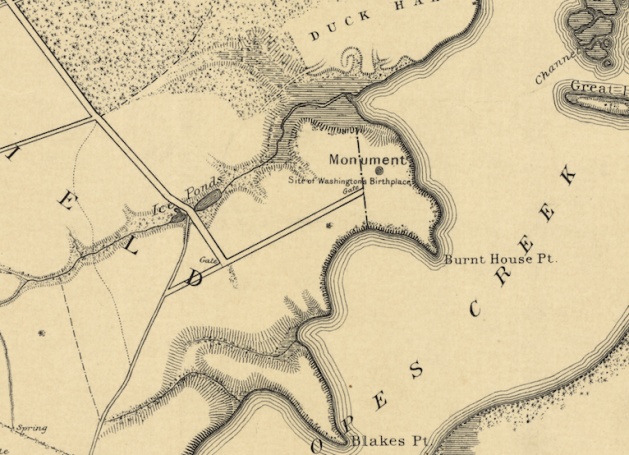

Returning to the 1897 USGC map shows a bit more of this site from a similar angle. What the map labels as “Monument” is the site of the Memorial House Museum. That straight road that runs away from it now extends all the way down to Rt 3. When this map was drafted though, visitors arrived by steam boat on a Potomac dock at the end of the straight road running to the left past the Granary.

The western border of the Washington land Lamkin surveyed was the road he called the Road to the Burnt House–it is the backwards L I have highlighted in this close up photo. The ultimate destination and name of that road is a question in and of itself, but for now, let’s focus on the spur that breaks off to its south–also highlighted here. Lamkin called this eastbound spur the Road to Washington’s Mill. Indeed, there was a mill at the head of Pope’s Creek for ages–the remains of its 20c iteration are still there to be seen. The area is now called Potomac Mills–not be confused with the giant mall on I-95 near DC. Right where Lamkin has written “Washington’s” there is another road forking with a spur headed back westward–making for a sort of backwards Z of a road.

The western border of the Washington land Lamkin surveyed was the road he called the Road to the Burnt House–it is the backwards L I have highlighted in this close up photo. The ultimate destination and name of that road is a question in and of itself, but for now, let’s focus on the spur that breaks off to its south–also highlighted here. Lamkin called this eastbound spur the Road to Washington’s Mill. Indeed, there was a mill at the head of Pope’s Creek for ages–the remains of its 20c iteration are still there to be seen. The area is now called Potomac Mills–not be confused with the giant mall on I-95 near DC. Right where Lamkin has written “Washington’s” there is another road forking with a spur headed back westward–making for a sort of backwards Z of a road.

This NPS commissioned painting is a fine representation of the fanciful landscape as imagined by the 1920s folks, here painted with newer understandings of outbuildings layered onto it. It is not a bad vision of an 18c Virginia plantation–it’s just that it is composed of made up parts. No such plantation existed here. The painting shows the fanciful 1920s Memorial House Museum as the Washington home. It was not. In fact, there was very little actual research that went into its building. It was a vanity project by an autonomous group of commemorators and the home looks like a cross between Gunston Hall and Twifford which was the home of the main backer’s grandmother.

This NPS commissioned painting is a fine representation of the fanciful landscape as imagined by the 1920s folks, here painted with newer understandings of outbuildings layered onto it. It is not a bad vision of an 18c Virginia plantation–it’s just that it is composed of made up parts. No such plantation existed here. The painting shows the fanciful 1920s Memorial House Museum as the Washington home. It was not. In fact, there was very little actual research that went into its building. It was a vanity project by an autonomous group of commemorators and the home looks like a cross between Gunston Hall and Twifford which was the home of the main backer’s grandmother.

Recent Comments