Here’s how this worked. A surveyor and his assistants would walk or ride the “metes and bounds” of a property noting the distinguishing landscape features that defined the various corners and limits of a property. Sometimes the border was a creek. Samuel Lamkin’s 1813 survey of the old Washington lands at GeWa for example, began his survey at Bridges Creek and then followed the run of “the said creek the several meanders thereof.” Other times it was a road or fence. A survey would often include notable landmarks like the “red oak at Pea Hill Gate” Lamkin singled out because any local would know just what he meant. Other times a party might make their own marks when nothing obvious was in sight.

The opening lines of Samuel Lamkin’s 1813 survey as reprinted in 1859.

Three Chopt Road west of Richmond, Va for example is named for just such a surveyor’s mark. Not all markers survived though. Seventeenth-century surveys of the area that became Williamsburg, Va often referred to a now-long-lost large stone. No has ever located that exact spot adding a fun element of guess work to understanding property lines.

The game then was for the survey team to measure the direction and distance between each point as the team came upon them. So a survey was more in the form of what used to be called a “rudder,” — a verbal and numerical description of a walk over the land. Again from Lamkin: “Thence S 42 ½ [degrees] W 16 poles to Wakefield Gate at H.”

The next step was to “plat” the survey–to draw it as a map: to change the words to a form of art. Not all surveys were platted, but plats are among my very most favorite forms of documents around. The best have the survey written on them as well so you can sort of trace out the path yourself. These documents are full of detailed landscape information while giving us the opportunity to see the land as it was understood and prioritized in the past.

We are lucky that the Washington land had several surveys and plats over the years. These are vital tools in reconsidering the place and making it all make sense.

One of the earliest is the Robert Chamberlain’s 1683 map of the land that shows the location of John Washington’s (1631-1677) house on the right in relation to the Potomac River at the bottom of the map. The play is a masterpiece of the art form. From the compass sign to the little symbolic houses (stay tuned for a post about those), this is master craftsmanship here.

Robert Chamberlain, 1683

Not all plats are as clear as this one though. The Library of Congress has an obscure collection of Washington related documents that bear on the GeWa story. Take a look at this crazy plat and see if you can understand it. It represents a subdivison of what should be Washington and neighboring land from sometime in the early 18c. The waterway on the right is the Potomac. Note how the drafter has used hash marks to indicate shore lines. He has made the river rather narrow and shows the Maryland shore on the far right. But look at how those hash marks work along Pope’s Creek on the bottom of the map. See the problem? I guess this is the first survey plat By M. C. Esher.

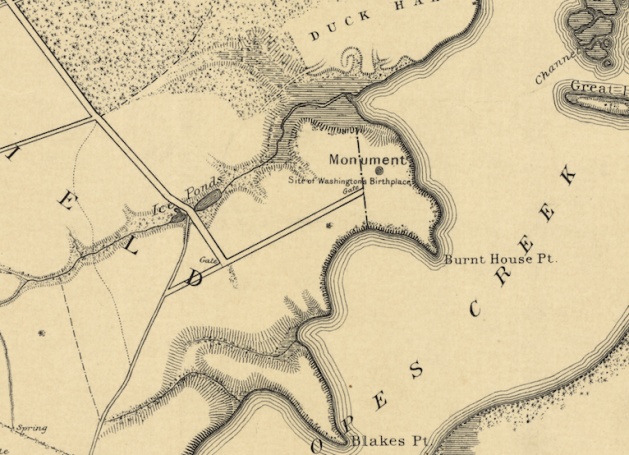

Samuel Lamkin’s 1813 plat and survey is one of the most useful documents for trying to figure out some site mysteries. This is one we will return to again and again as I blog this project.

Samuel Lamkin, 1813

This NPS commissioned painting is a fine representation of the fanciful landscape as imagined by the 1920s folks, here painted with newer understandings of outbuildings layered onto it. It is not a bad vision of an 18c Virginia plantation–it’s just that it is composed of made up parts. No such plantation existed here. The painting shows the fanciful 1920s Memorial House Museum as the Washington home. It was not. In fact, there was very little actual research that went into its building. It was a vanity project by an autonomous group of commemorators and the home looks like a cross between Gunston Hall and Twifford which was the home of the main backer’s grandmother.

This NPS commissioned painting is a fine representation of the fanciful landscape as imagined by the 1920s folks, here painted with newer understandings of outbuildings layered onto it. It is not a bad vision of an 18c Virginia plantation–it’s just that it is composed of made up parts. No such plantation existed here. The painting shows the fanciful 1920s Memorial House Museum as the Washington home. It was not. In fact, there was very little actual research that went into its building. It was a vanity project by an autonomous group of commemorators and the home looks like a cross between Gunston Hall and Twifford which was the home of the main backer’s grandmother.

Recent Comments